Government’s Closed-Source Intelligence

Jun 18 2014 / 7:19 pm

By Philip Giraldi.

The American Conservative – In a recent discussion I had with Scott Horton on his radio show, we speculated as to why the White House, which surely includes very many smart, hard-working, and responsible people, just cannot seem to recognize the cognitive dissonance inherent in supporting contradictory policies in places like Syria. Supporting the “rebels” in an effort that will likely fail to bring down the government in Damascus only prolongs the suffering of the Syrian people, while, if by some chance the insurgents actually did win, it would mean the death of the once-vibrant Syrian Christian community and the likely installation of a fundamentalist terrorism-supporting regime in the heart of the Arab world that would make its counterparts in Saudi Arabia and Iran look positively libertarian. And that support comes at the immediate price of the bloody disintegration of neighboring Iraq.

We eventually came to the conclusion that the staffs in large bureaucracies are not necessarily selected for their independence of mind. Quite the contrary, they rise to the top because they learned in grade school to get along well with others, which in practice means that groupthink will always prevail even if it is highly illogical and in the long run damaging to genuine interests. Combine that with an essentially reactive foreign policy, and you have a formula for coming to the wrong conclusion nearly every time.

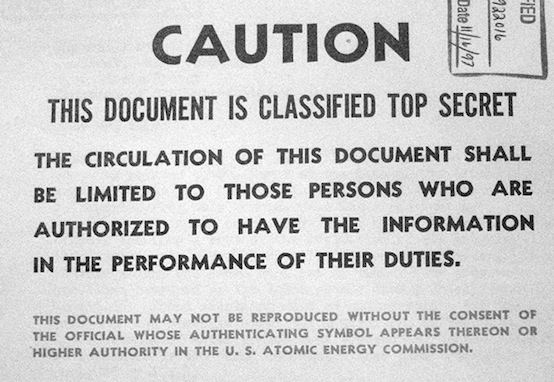

But the old garbage in-garbage out rule should also be considered. Having been in U.S. intelligence myself, I can confirm that officials tend to regard classified information as reliable and comprehensive, which frequently leads them to ignore everything else. It might be comforting to peruse a glossy report stamped “Top Secret” in the National Security Council conference room, but from my role as an intelligence collector overseas I can assert without any fear of contradiction that clandestine source reporting can be as bad as what one reads on just about any site on the Internet, and is often considerably worse than what appears in the newspapers. This bias in favor of reporting produced by the “community” induces a tunnel vision on the part of intelligence analysts that has belatedly led to a debate about the value of open sources versus the tightly controlled version of reality that prevails in security clearance land.

Unfortunately, government bureaucrats don’t really see the quality of finished intelligence as an information issue. They tend to take steps to shut out unwelcome reports rather than including them and weighing their validity. This is because their prime objective is to control the story being fed to the public and the media. As most of the world currently obtains its information from news services and Internet sources that are beyond the control of any one government, various mechanisms have therefore been exploited to limit the ability of the public as well as government employees themselves to circumvent established narratives being promoted to support specific policies. Recently in Turkey, the government took steps to shut down Twitter accounts that enabled protesters to report independently on police activity. Similar limitations on access to Internet-based social media have been put in place in Egypt, Syria, Iran, and China. The United States has even proposed legislation to turn off all Internet communications in the event of an as yet largely undefined state of emergency.

As a better informed analyst will presumably write better reports, some recent steps taken by the U.S. defense and intelligence communities to treat clearly true leaked information as lies are particularly hard to comprehend. As long ago as late 2010, the Pentagon forbade any employee from visiting the WikiLeaks website. The White House and the Air Force subsequently broadened the prohibition, issuing both an executive order and command guidelines blocking the use of either office or home computers to view sites that contained WikiLeaks-derived information. The ban, which in its Air Force version initially even included family members, ironically confirmed that the information revealed by WikiLeaks was accurate. It also prevented many government employees from reading the New York Times, among other publications, which had unanticipated consequences. While the entire reading public was able to know, for example, that in 2009 the United States had initiated a spying campaign targeting the leadership of the UN in violation of the 1946 United Nations convention, Pentagon intelligence analysts were presumably officially ignorant of that fact.

The unconvincing excuse provided by an Air Force spokesman to justify its draconian measures was that the classified information in the news articles would contaminate the unclassified computers being used to access the news sites, requiring that the computers be sanitized before they could be reused. In other words, information that has once been classified and is now in the public domain is still considered secret if pulled up on a U.S. government computer and read by a government employee. Employees were also advised that they would receive a security violation if they were detected using home or personal computers to view classified material available on public sites, because they had no “need to know” the information.

While most Americans would agree that there are legitimate secrets, the flood of information revealed by WikiLeaks, Bradley Manning, and Edward Snowden suggests that, in some cases at least, classification has been used to conceal either illegal activity or actions that might widely be condemned as inappropriate if revealed to the public. As a result, the belief that the U.S. government mostly acts in the national interest has been replaced by a growing conviction that the government’s own bureaucratic interests and those of the public it purportedly serves have largely diverged.

The latest attempt to clamp down on leaks of information was briefly reported in the New York Times on May 8th. In April, the Office of Director of National Intelligence James Clapper issued an updated directive as part of its so-called “pre-publication review policy,” which requires employees as well as many ex-employees to clear in advance speeches, articles, books, and any other unofficial writing, including letters to newspaper editors. Clapper, who is perhaps best known forlying to Congress about the extent of the National Security Agency surveillance program, has now banned current and former employees from including any references to news or media reports based on leaks of classified information. The reasoning? “The use of such information in a publication can confirm the validity of an unauthorized disclosure and cause further harm to national security.”

The new policy, which does not even permit the mention of an article, is widely seen as an attempt to discourage whistleblowers. It is an expansion of the authority granted in a Clapper policy statement issued in March that forbade any substantive contact with journalists, even if the information being discussed were unclassified, which would appear to be a clear violation of First Amendment rights. Ironically, the sweeping ban also makes it impossible for former employees to debunk information in the public sector that is manifestly untrue, as they cannot even mention an article in order to deny its credibility. As one critic noted, government employees “can’t talk about what everyone in the country is talking about.”

The government claims that pre-publication review is not a closed door, and that articles are frequently cleared after it is determined that there is no classified or “sensitive” content, but the reality is that writing critical of the intelligence community has historically suffered trying ordeals in the clearance process, while works that praise the government are ushered through. George Tenet, former Director of Central Intelligence, researched his book At the Center of the Stormusing classified documents in a secure room provided by contractor SAIC with the full cooperation of government agencies, while Jose Rodriguez, who headed the CIA torture program, also was able to have his book Hard Measures, which justified his questionable decisions, approved without any major redactions. Other authors who have been more critical, including Ishmael Jones, have been houndedboth by CIA and the Justice Department.

The information being protected is not even necessarily classified. The new guideline replaces the old standard of “protection of classified information” with preventing “the unauthorized disclosure of information.” The new rules would also cover how the intelligence agencies conduct their business, including revelations of criminal fraud and waste. The government deliberately writes its rules ambiguously to give itself a free hand to interpret what is or is not considered a violation.